As someone with dissociative identities, I have found trying to access support and gain understanding about myself a real challenge. The word dissociation was used for the first time when I was 21 years old to explain what was happening for me. It made no sense to me why I could go from being so happy and well in the morning, to being acutely suicidal in the afternoon, or finding a random jumble of distressing notes in my phone I didn’t really remember typing. Anxiety, depression, anorexia, and borderline personality disorder were the labels I was given (among many, many others) over the years in trying to seek support. Services designed to offer care often perpetuated harm through misunderstanding dissociation. Unfortunately I was also subjected to inhumane treatment during inpatient psychiatric admissions, as well as being sexually abused by a health care professional.

For me, learning I had dissociative identities was life changing. I began to find my parts and was able to start communicating with them. Nine years later, I am happy to report I can maintain dual awareness with all my parts and we have come a long way in our understanding and acceptance of each other. I rarely have amnesia these days and when other parts do take the driver’s seat I am still there as a leader able to communicate and collaborate with them most of the time. It is very different and life is a lot easier and happier.

When I first heard about dissociation being a potential explanation for my experience I was very scared. My only experience with dissociation was through the media, where Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is dramatised for the entertainment and consumption of others. Such content often depicts people with DID as serial killers. This is so damaging to people like me who are doing our best to get by. Having multiple distinct parts with different ages, genders, interests, core beliefs, and more is very confusing! On top of this, we also need to deal with the stigma of how dissociation is perceived by the public. There is still to this day debate among academics about whether our condition is even real. I would challenge anyone with views about DID being fictitious to come live in my head for a day and listen to the chattering between parts!

In the early days of trying to understand myself, therapists were too scared to use the label of DID. Instead, I was simply called “dissociative” and was left with many unanswered questions. Largely through my own research and training, I slowly realised there was more going on for me. It took many years for a therapist to be brave enough to list DID as my diagnosis on paper. However, the result has honestly been life changing. Before this, I believed I must have been making my symptoms up or that surely I was making a big deal out of nothing. For me, diagnosis confirmed what I had already known since early childhood; there is more than one person inside my mind. My perception of myself and the world now felt valid because I had a word to describe and make sense of my experiences.

Having dissociative identities can be very lonely. How do you tell other people you don’t “feel” like one person? How do you validate the needs of all parts which can be so highly different and confusing? It can feel like you are so different to other people and that no one knows how to help you, especially because there are few therapists who are willing to work with us due to fear or lack of understanding about how to help us.

Throughout my journey, I struggled to find psychoeducation or resources that were relevant or helpful. Information about dissociation is often aimed at clinicians (e.g., professional development courses or textbooks) or has been created by people without lived experience of dissociative identities themselves. The information I could find gave me an initial understanding of dissociation and was helpful for supporting parts who were trying to cope with their trauma in more harmful ways (e.g., drinking). At the same time though, the language used in many of these resources often made me feel like I was insane, defective, or worse. I began to internalise ideas about needing to ‘integrate’ all parts to be considered ‘whole’, that I was wrong for naming my parts because I was “creating alters”, and that I needed ‘treatment” to ‘stop’ dissociation from occurring. Ultimately, I learnt that dissociation was inherently wrong, and this only contributed to shame and panic whenever I heard my parts inside.

Through reading, connecting with others who have lived experience of dissociative identities, and engaging in many therapeutic modalities, I have come to the realise that many of those messages about dissociation were incredibly harmful and stalled my healing journey. It has taken many years, but I finally have the confidence to trust my own intuition about frameworks, strategies, and modalities that feel “right” to us as a system of parts. I have a few parts in particular who resent the idea that they aren’t ‘real’ or valid compared to what is seen as the “core” part. They have been treated as though they are ‘blocks’ in therapy, a hinderance, and a defence mechanism, rather than essential parts of who we are, despite saving our life repeatedly!

As a therapist (and especially as an EMDR therapist), I completely understand the fear of not wanting to make mistakes or cause more harm with dissociative clients. I also believe it is very important we all practise within the scope of our own competence. However, the way I hear DID spoken about in trainings really sends chills down my spine and I would love for people to become more comfortable in understanding how to work with us, or at the very least not be afraid of working with us.

Every human has parts. Some of us just have more barriers and amnesia between our parts or they are more distinct. People who have dissociative identities have had horrific experiences and have developed an intricate internal system of parts to survive extremely unsafe people and situations. As clinicians, we need to honour the incredibly important roles of our client’s parts, rather than seeing them as enemies or frustrating barriers or blocks to treatment. Even if you are unable to proceed with long-term trauma therapy, simply providing psychoeducation and beginning to support understanding of dissociation is such a valuable start. For me, beginning to make sense of what was happening for me helped me become more empowered and kick-started the process of healing.

Working with someone who has dissociative identities can be long and hard work, both for the therapist and the client. We can often present with high-risk coping behaviours and may be inherently distrusting of therapists (often due to negative experiences when seeking help in the past). Even if you are only with a client for part of their journey, you have the power to keep promoting their healing by accepting them and, in doing so, help them to understand themselves piece by piece.

Be curious about your client’s parts. Hear them out and understand their experiences and perspectives. Support parts to be-friend each other internally, and establish compassionate relationships within the dissociative system. Do not try to get rid of or banish parts. Your modelling of how to accept a client’s parts can demonstrate that all are welcome. This creates safety. People with dissociative identities are often highly fearful of their parts and emotions. We have been taught sides of us are not allowed or are to be feared or shut away. My healing journey really began when I met an incredible therapist who treated all parts of me with compassion. No part was shamed or condemned, even if some of their ways of coping were harmful at the time. Rather than being punitive, my therapist understood the trauma all parts were holding and approached them with unwavering kindness.

I have worked with over 25 therapists in my life. My trauma history is extensive and seeking help for my mental health has been highly traumatic in and of itself. However, I can safely say I am still here because of some incredible, talented, and (most importantly) compassionate therapists who have helped me along the way by believing my lived experience was valid and hearing me. When my therapists allow my parts to be in the therapy room and demonstrate acceptance, I feel safe to show more of myself and collaboration increases.

I am by no means “integrated” and do not like this term. Rather than integration, I prefer the word I first heard used during a presentation by Dr. Jamie Marich’s; Unification. This word resonated in a profound way for my system of 10 parts. Rather than feeling like we have to be one person, all parts simply want to live with less distress. We want to be able to work together flexibly when needed. We want to accept and value each other, including the roles we have all had to play to keep us alive as a system. We like all the different interests, skills, and insights were offer each other and truly believe it would be to our detriment to shut any part away! Things aren’t perfect, but shifting our way of thinking about healing to this perspective has been groundbreaking and has greatly increased our quality of life as a system.

I hope that sharing my lived experience and insights can offer a different perspective about dissociation. The fact is that there are many therapists who do live with dissociation themselves, but fear speaking about their experiences due to how this may be perceived. If the stigma remains unchallenged we risk losing the opportunity to learn from those who could help us most in understanding how to support dissociative people.

2 Responses

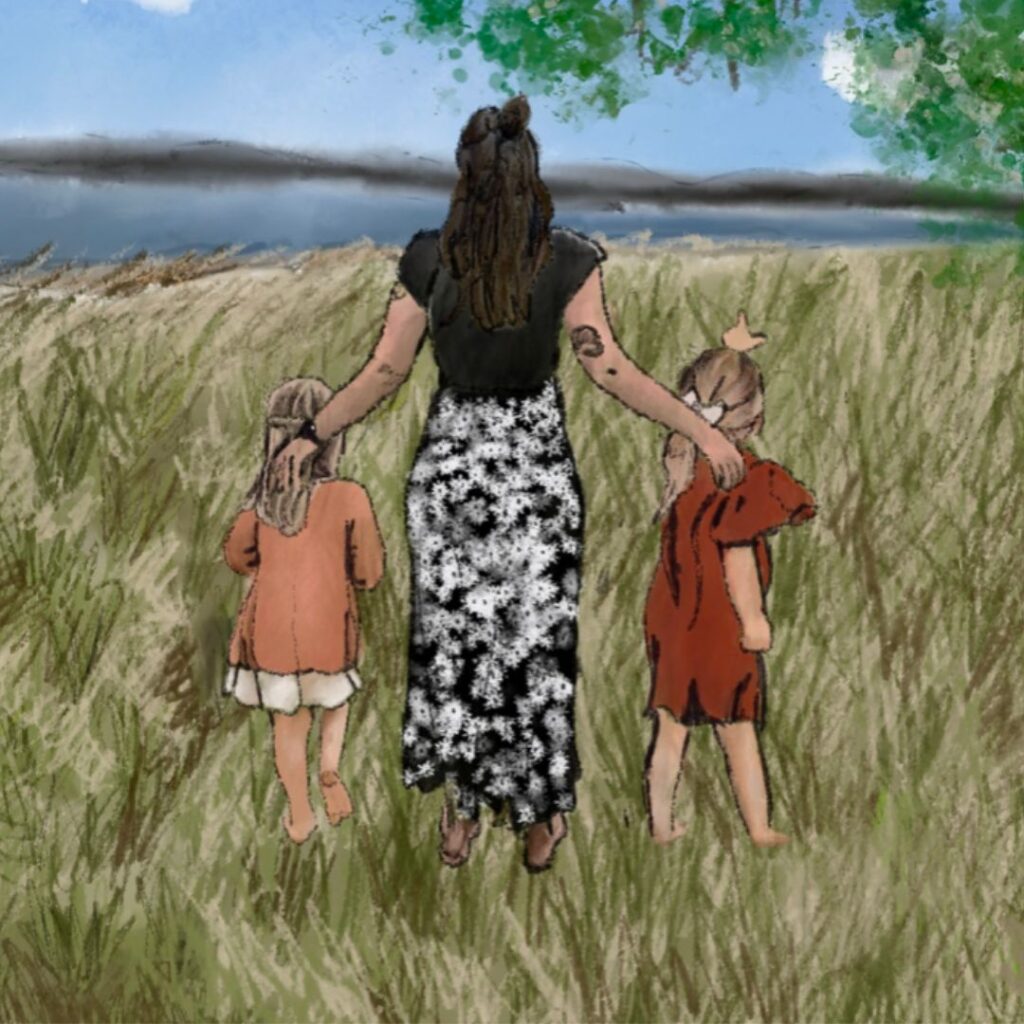

Thank you for sharing your experience as both a client and therapist- we love the artwork as well

Thank you very much for sharing your experience and your thoughts! I learned about dissociation from Ellert Nijenhuis. If you know his work, may I ask you, what you think of his ideas on dissociation from your lived experience perspective?