(CONTENT WARNING: This contains personal recollections of childhood sexual abuse, fat shaming, and eating disorders.)

A few years ago, I decided it was time for a new therapist. Naturally, that led to the painful experience of retelling my story of abuse, neglect, addiction, and poor decisions. The more I spoke, the more I felt like a hot mess living in the middle of a raging dumpster fire. Toward the end of the session, the therapist paused with a puzzled look and asked how I was able to function as a fairly well-adjusted adult. Her question caught me off guard as my mind was still fixated on the dumpster fire. I don’t remember exactly what I said. In retrospect, I have been in therapy on and off for years, my social support system is incredible, and I was born with a brain that instinctively used dissociation to survive the unthinkable.

While all people dissociate to some degree, my experience can be best described by the diagnosis of Otherwise Specified Dissociative Disorder (OSDD), similar to Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). In essence, my amazing brain can erase traumatic events from my conscious mind. Time occasionally disappears. I can also turn off both emotional and physical pain. On the flip side, the world around me can look terrifyingly distorted and feel unreal. Before learning about dissociation, my only personal explanation was that I had a brain tumor even though the MRI and neurologist said otherwise.

When I began in-depth trauma therapy and my inner numbness began to lift, the presence of parts became front and center. I went from shock to denial, then back to shock. I am a therapist and once believed the myth that DID and OSDD are extremely rare. I will refrain from going on a tirade about the stigma and false beliefs associated with these diagnoses. Instead, I stand boldly as a licensed professional counselor who happens to be a system of parts.

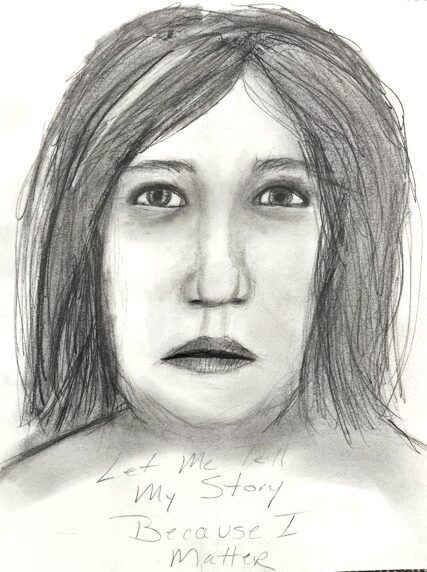

Being transparent is not easy. It goes against the well-ingrained rules I grew up with of don’t talk, don’t think, don’t feel. I fear fellow clinicians will see me as unfit to practice and disclosure could negatively impact my career. Yet, most who enter the mental health treatment field have experienced some degree of trauma and mental health challenges. It is our personal responsibility to learn, heal, and grow so as not to be a detriment to ourselves and others. Counselors need counselors. The therapy I have and will continue to receive provides a depth of understanding that cannot be taught in a class, conference, or webinar. Today my lived experience and healing journey is not a professional liability but a strength. I share my story to help demystify clinically significant dissociation and illustrate how a system of parts working together can bring amazing resiliency.

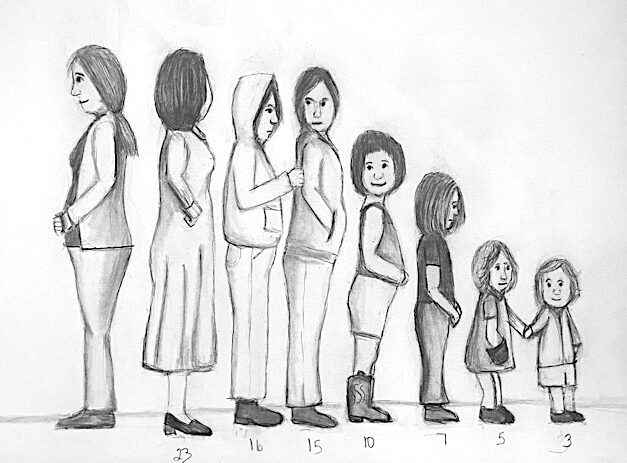

My life made more sense once I acknowledged and embraced all the parts of me. In retrospect, I have been a system of parts since a child. For example, I always wondered why I would be extremely outgoing one moment and painfully shy the next. My ability to play the piano proficiently comes and goes. Most of the time I enjoy being in front of a crowd teaching or performing, and the next moment I am in a near panic or become overly playful. Why do my scores on personality tests like the Myers Briggs change like the direction of the wind? I always felt the presence of younger parts, a self-destructive part, others who felt scared and unheard, one who is playful and loves all things pink and sparkly, and another who is a highly competitive overachiever. At this time in my life, I have 8 primary parts inhabiting this middle-aged woman’s body. Most are younger versions of myself with ages that correspond with times of great distress. Each has a job or role with unique talents, weaknesses, likes, and dislikes. My brain is not broken or shattered into many pieces. Rather, it is greatly compartmentalized and complex, enabling me to best function as a human who survived the unthinkable.

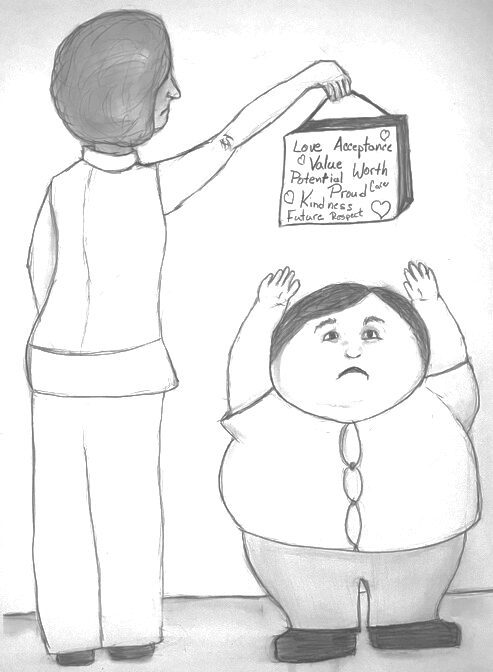

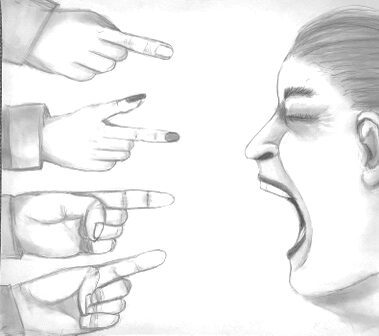

Deep down I always knew that I could draw. It was puzzling because the only things I could produce were cattywampus stick figures reminiscent of an elementary school art project. Once my parts came into focus, this innate ability appeared out of nowhere. The style is partially dependent on who has something to say. Some parts have a more cartoonish style while others prefer realism. My angry part likes dark charcoal and messy oil pastels. Through their art, I, my most adult self, can see their face, understand their role, and listen to their heart. With their permission, I have included some of our drawings.

A person does not develop clinically significant dissociation without childhood trauma. I grew up among sexual perpetrators. That was coupled with physical violence, neglect, and other experiences I’m not ready to disclose publicly. There was one common factor. I was a chubby kid and nearly all my abusers made derogatory comments about my body.

I grew up with intense pressure to lose weight. When bullying and fat shaming didn’t work, they tried different approaches. In 6th grade, I wanted to wear popular, brand-name jeans. I was given multiple pairs, all 2-3 sizes too small in hopes it would motivate me to lose weight. This and other events instilled a myriad of negative beliefs such as I’m not good enough and I’m an embarrassment. While I desperately wanted to feel loved and accepted, food such as sugar-filled breakfast cereal, frosting, cookies, and boxes of Pop-Tarts had already become a soothing and powerful drug. It provided a pleasurable numbness that enabled me to endure.

As my body changed during puberty, the abuse intensified. I clearly remember being 15 and looking out the window shortly after an episode of abuse. At that moment, I made a conscious and deliberate decision to gain a large amount of weight in hopes that my body would become unappealing. Safety was more valuable than the emotional cost of fat shaming and bullying. I will never know if this strategy worked as a deterrent. With full certainty, I know self-hatred grew with every pound gained.

Like many with eating disorders, it morphed over time with occasional periods of remission. Binge eating turned into bulimia. When my weight became higher than I desired or felt the need to self-harm, I shifted to over-restriction. Binging was a quick way to dissociate from the present moment. Purging provided a euphoric high, comparable to any drug. It made my life tolerable. I couldn’t stop, nor did I want to. It was an addiction.

Bulimia followed me to college and into adulthood. I majored in vocal music performance for a while. During the winter of my junior year, I bravely stepped outside my comfort zone and accepted a role in an opera. This was thanks to my 16-year-old part who is a natural performer and highly competitive. Fifteen, who is typically anxious and prefers to be seen as gender-neutral, shuttered because it involved being on stage in a very feminine costume, dancing, and playing the role of a love-crazed woman. The opera required a great deal of courage along with weeks of intense preparation and endless hours of rehearsals. I was proud of the final production. More so, I felt empowered because I successfully faced my biggest insecurities. I brought the recording home to show my parents, hoping to receive praise. My dad sat in front of the TV and immediately pointed out how fat I looked on stage, laughed, and made insulting noises when I danced. I was crushed. All sense of pride and safety was replaced with shame. My parts have not allowed my body to dance since that day. I also became more dependent on the dissociative effects of bulimia while new addictions emerged.

The work of Dr. Adam O’Brien and Dr. Jamie Marich with Addiction as Dissociation resonates strongly with me. In essence, engaging in addictive or compulsive behaviors enables a person to separate or sever from their thoughts, body, and/or emotions. This is a hallmark throughout the continuum of dissociative experiences. I compare the effects of trauma and great distress to driving through a torrential rainstorm. It is chaotic, the road is hard to see, and real or perceived danger can jump out of nowhere. Dissociation related to addiction is like going under a bridge or overpass. The rain stops, it is quiet, the world looks clear, and for a moment everything feels tolerable. This dissociative bliss is short-lived as the car inevitably re-enters the raging storm.

Through eating disorders and other addictions, I desperately searched for the next overpass or a break in the clouds to separate myself from the overwhelming anger, pain, and life-interrupting symptoms of complex PTSD. It was a tool. It may have saved my life when waves of suicidal ideation hit. It also left destruction in its wake.

Addiction and eating disorders were costly in both tangible and intangible ways. I eventually found myself living in a 5’2, 318-pound body while navigating a life of shame, secrets, and self-hate. After many attempts and broken promises, I gradually stepped off the rollercoaster of destruction and consider myself a person in long-term recovery. Even though the self-destructive behaviors stopped, I was left with the aftermath.

Trauma was addressed early in my recovery, but the numbness related to dissociation prevented me from touching intense emotions and memories. Years later, Eye Movement, Desensitization, and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy enabled me to dive into the painful areas and destructive core beliefs that kept me bound to my past. Instead of crumbling or shutting down, strength and a sense of freedom began to grow. My colleague Adam O’Brien described a desired outcome of EMDR as being able to talk about the worst day of your life as if it were Wednesday’s lunch. The healing I experienced using EMDR changed my life and fortified my recovery. Ten is learning to be her genuine, silly self. Sixteen, the over-achieving performer, is learning to rest. Fifteen is finding her voice. As a system, we are more confident, assertive, playful, and creative.

During an intense EMDR session, I looked down at my lap and had an epiphany. “I no longer need to be covered by an extra 150 pounds of flesh to feel safe. My weight is a visible scar from years of trauma.” This was very jolting because my system’s usual go-to response for anything diet or weight-related was to get overly angry, say something snarky, and shut down. No matter the intention, any mention of my size stung like pouring rubbing alcohol into a deep wound. Far too many people have tried to convince me to lose weight including my abusers, doctors, and even a well-meaning hairdresser who told me to eat only cucumbers and cantaloupe. This extra layer of flesh was my protective forcefield that kept people away. How could I survive without it? Denial of my weight was fed by avoidance cameras and mirrors. The non-diet, listen-to-your-body philosophy of intuitive eating worked very well. Most notably, I and the rest of my parts didn’t want to touch the tremendous amount of shame and hate we had toward our physical self.

As EMDR therapy and healing continued, my defiant emotional response melted enough to look at things more objectively. I acknowledged that the original and ongoing purpose of my weight was to hide. This was in direct opposition to my even larger desire to live boldly as my most authentic self. The picture became clear. The next step in my healing journey was to allow my physical body to catch up and reflect the transformative, internal healing I and the rest of my system were experiencing.

Historically, attempts to lose weight failed, negatively impacted my mental health, and threatened my recovery. This time I needed to make some well thought out decisions. I, my most adult self and leader of the pack, gathered my parts together for a meeting. Some refused to show up. Some were angry. Others were afraid, numb, or indifferent. I explained that we were going to change our body’s size and shape while being respectful and kind to our physical self. They didn’t have much to say. My decision was firm.

I strategically put together a dream team of professionals to help me/us with this journey. I found an amazing, non-judgmental physician who instilled hope and provided concrete ways he could help. Ten and Fifteen adore him. I also found a dietitian familiar with eating disorder recovery and continue to see my EMDR therapist. Finally, I found a personal trainer who is also a seasoned therapist and a person in long-term recovery. My dream team challenges me while providing direction, encouragement, and accountability.

A few months into this journey Fifteen became overwhelmed with feelings of fear and vulnerability. It made sense. She was the one who decided to gain a large amount of weight to hide from dangerous people. Most urgently, Fifteen needed to feel safe enough to be around our male personal trainer. During our next session, I timidly sat down on the weight bench, took a deep breath, and told him about our parts and the myriad of ways we dissociate. He wasn’t shaken. Instead, he kindly asked what we would like him to do when it happens. What an amazing and non-stigmatizing response! That made Fifteen feel safe enough to test him with our story of trauma and explain how we want our outer self to match our healing inner self. He smiled brightly and said, “Well, let’s make that happen!” We never felt so empowered.

As I and the rest of my parts navigate through this journey, there are moments when we feel on top of the world. Other times we feel emotionally beat up. Changes in our size and shape have led to the emergence of more traumatic memories, intense emotions, and an array of somatic responses. Sixteen wants to micromanage everything we eat and needs to be reminded of the 12-step slogan, “progress, not perfection”. Ten is overly obsessed with shopping for cute, smaller-sized clothes. Fifteen has been dealing with a lot of anxiety and needs someone to listen to her. An older, angry part will spew words of discouragement. My most adult self works hard to maintain stability within the system and avoids triggering words like “dieting”, “skinny”, or “fat”. Instead, we say health and transformation. Despite the obstacles and ongoing challenges, we refuse to give up.

Publicly embracing our dissociative mind, sharing our story, and shedding the physical manifestation of childhood trauma is getting us closer to the ultimate goal, to live boldly as our most authentic selves. Occasionally I pause in front of the mirror with a sense of awe as we see our genuine physical self gradually emerge from hiding. This much smaller person is stronger and more tenacious than the one who initially walked into the therapist’s office feeling like a hot mess living in a raging dumpster fire. Ten can now get on the floor and play. Sixteen wants to run a 5K even though it would harm these middle-aged knees. Fifteen looks at our body, smiles, and realizes she has a lot more healing to do. My most adult self stands boldly with a message to share about healing, post-traumatic growth, and the realness of being a therapist living with a dissociative mind.

In February 2024 we quietly celebrated our unannounced milestone of losing 100 pounds without reverting to addiction and disordered eating. Instead of celebrating with food, this body walked 10 miles in a theme park, sat comfortably on rides, and attended a conference about dissociation where we met more people like us. Maybe one day my parts will allow this body to dance again. I certainly hope so.

Sarah Joy

This author is an ICM grad, EMDR Consultant-In-Training, and completed the Advanced Certificate in Dissociative Studies for EMDR Therapists. While she longs to use her real name, this author has chosen to remain anonymous until it is safe enough to do so at her place of employment.

6 Responses

Thank you for sharing your authentic experiences! We know your lights are shining into the darkness for others.

Thank you so much for your vulnerability and authenticity. You are an inspiration. 🤍

You are beautiful. Thank you for your wonderful post. Sending love to all your parts. I hope your parts feel safe enough soon to take that first dance. ♥️

Beautiful story. Thank you… thank all parts of you for sharing.

Wow! Wow!!! I am on holy ground as I read and “live” some of your story. Blessings to all of who you are and all of who you will continue to become.

Well done. Admired for your courage. Sharing your experience made me think about my story.