We hear a lot about the dangers of being judgmental in many wellness and recovery circles. And in a colloquial sense it speaks to us. No one likes a judgmental jerk. That person who constantly insists they are right in all matters and anyone who doesn’t conform to their beliefs or way of doing things is somehow less than, fundamentally wrong, or just plain stupid. Many of us probably judge ourselves more than others, beating ourselves up with negative self-talk. I’m guilty of telling myself I look terrible in this photo, or chastising myself for not getting some important task completed earlier. We can even internalize these judgments so much that we suppose we are bad people at our core.

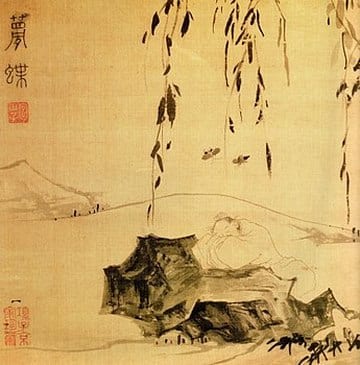

So much has been written about the problems of being judgmental and how we ought to suspend judgment or stop it all together. With all the problems surrounding judgments and all the pain it can cause us, I am still going to propose something a little radical: The ability to make judgments, and discernments, may just be an innate fact about the human experience. And maybe, just maybe, it’s not necessarily such a bad thing. To explain myself, I’d like to refer you to my favorite classical Chinese text, the Zhuangzi. Zhuang Zhou, from whom the text takes its name, lived in the third century, BCE in ancient China. The book that bears his name is a delightful romp of riddles, vivid imagery, talking animals, meditations on life and death, and some really well thought out discussions about why we humans run into trouble with one another and ourselves.

First, a quick biology lesson according to ancient China: the heart (xin 心) was considered the seat of both cognition and emotion. Today we often talk about the difference between the intellectual or rational brain and emotional heart. For the Ancient Chinese, there wasn’t a qualitative difference. The heart was considered the seat of both thinking and feeling. Insofar as the heart was responsible for intellectual thought, it was thought to issue judgments. More accurately, the heart picks out things in the world discerning them from other things. For example, it deems this keyboard I’m typing on to be distinct from all of the other non-keyboard things surrounding me, like my desk or the accumulated dirty coffee mugs, receipts, and folders. Zhuangzi talks about the heart’s picking things out, or the judgments we make, in terms of Shi (是) and fei (非). When I shi something, I’m affirming it – it’s like saying “THIS keyboard!” When I fei something, I’m denying it, like saying as I point to my coffee mug “THAT IS NOT the keyboard.” These judgments are how we organize our world. They are how I know which road is safe and which is not, what things are poisonous and which are edible, what person, place or thing might be harmful, and which are helpful. The very act of making judgments is an innate a useful tool of the human psyche, straight from the heart.

Zhuangzi recognizes that these judgments aren’t without their problems. A stark fact about these judgments is that they are fundamentally dependent upon a person’s perspective. For example, standing nearer to a mountain, I would judge it to be large, while you, further away, look at it think, “gee, that’s small”. Where we are, in the physical, historical, cultural, social, and emotional senses shapes our judgments. Given the context dependent nature of our judgments, and the belief systems, ideas and ethics they give rise to, Zhuangzi asks us to remember that shi and fei, this and that, right and wrong, are merely useful linguistic categories, and not absolutes. That’s where problems arise.

Zhuangzi explains, “If a man sleeps in a damp place, his back aches and he ends up half paralyzed, but is this true of a loach? If he lives in a tree, he is terrified and shakes with fright, but is this true of a monkey? Of these three creatures, then, which one knows the proper place to live?” (trans. 1968). What is ‘right’ from one perspective may not be applicable in all circumstances. Zhuangzi is concerned about the tendency toward over confidence in one’s capacity to make “correct” judgments, when in fact these judgments are not reflective of some mind-independent state of affairs. Ultimately this can lead to undesirable consequences. Using the text’s example, if the loach tried to enforce his standards upon a man, the man would end up half paralyzed! Zhuangzi cautions us about supposing that our judgments are absolutely right independent of ourselves. We find conflict when we suppose that what we have uncovered really is the case, instead of treating our judgments like the useful tools they are, helping us navigate and make sense of the world. Conflict occurs when we elevate those judgments to the level of doctrine.

Ultimately Zhuangzi asks us to “fast the heart”. What the heck does this mean? While there are plenty of academics who might disagree with me, I’ve got the sense he’s just asking us to mellow out. If it’s a biological fact about us that we make judgments, the heart also has the capacity to revise these judgments as we encounter new experiences and events in the world. It means that instead of issuing judgments and treating them like dogma, the proper use of the heart is to critically evaluate our beliefs, to help us think in new ways, to grow, to discard old ideas, and to constantly find better ways of making sense of the changing world around us. To me, fasting the heart means to quit feeding it BS that makes us feel like we need to have it all figured out, and instead be open to growth, changing our minds, and forming new ideas and judgments as we journey on through life. It means that everyone has a story, a background, and a context and it allows us to treat each other as human beings on a journey, rather than condemn them as fools who don’t or won’t get it.

Long before I’d ever read the Zhuangzi I remember being inundated with talk about judgments and being judgmental. On the one hand, I knew I could be a little snarky cynical, and it was true that those were areas I needed to improve upon. On the other hand, I felt like I had some brain power and how could it be the case that I wasn’t supposed to or equipped to make judgments? An incredibly wise woman told me, “You can judge all you want, that’s how to know to stick with the winners – the people who have something in their lives that you want. What you can’t do is condemn. The only time we look down on someone is if we are helping them back up.” It made a lot of sense to me at the time, but has only become more profound over the years. What she meant, and what I believe Zhuangzi intends to convey, is that life is tough enough already. We have the capacity and ability to find what kind of life works the best for each of us and grow and renew ourselves each day. If we can help someone up, rather than condemning them along the way, it makes the journey all the more worthwhile.

Reference:

Zhuangzi and Burton Watson (1968). The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu. Translated by Burton Watson. New York: Columbia University Press.

So much has been written about the problems of being judgmental and how we ought to suspend judgment or stop it all together. With all the problems surrounding judgments and all the pain it can cause us, I am still going to propose something a little radical: The ability to make judgments, and discernments, may just be an innate fact about the human experience. And maybe, just maybe, it’s not necessarily such a bad thing. To explain myself, I’d like to refer you to my favorite classical Chinese text, the Zhuangzi. Zhuang Zhou, from whom the text takes its name, lived in the third century, BCE in ancient China. The book that bears his name is a delightful romp of riddles, vivid imagery, talking animals, meditations on life and death, and some really well thought out discussions about why we humans run into trouble with one another and ourselves.

First, a quick biology lesson according to ancient China: the heart (xin 心) was considered the seat of both cognition and emotion. Today we often talk about the difference between the intellectual or rational brain and emotional heart. For the Ancient Chinese, there wasn’t a qualitative difference. The heart was considered the seat of both thinking and feeling. Insofar as the heart was responsible for intellectual thought, it was thought to issue judgments. More accurately, the heart picks out things in the world discerning them from other things. For example, it deems this keyboard I’m typing on to be distinct from all of the other non-keyboard things surrounding me, like my desk or the accumulated dirty coffee mugs, receipts, and folders. Zhuangzi talks about the heart’s picking things out, or the judgments we make, in terms of Shi (是) and fei (非). When I shi something, I’m affirming it – it’s like saying “THIS keyboard!” When I fei something, I’m denying it, like saying as I point to my coffee mug “THAT IS NOT the keyboard.” These judgments are how we organize our world. They are how I know which road is safe and which is not, what things are poisonous and which are edible, what person, place or thing might be harmful, and which are helpful. The very act of making judgments is an innate a useful tool of the human psyche, straight from the heart.

Zhuangzi recognizes that these judgments aren’t without their problems. A stark fact about these judgments is that they are fundamentally dependent upon a person’s perspective. For example, standing nearer to a mountain, I would judge it to be large, while you, further away, look at it think, “gee, that’s small”. Where we are, in the physical, historical, cultural, social, and emotional senses shapes our judgments. Given the context dependent nature of our judgments, and the belief systems, ideas and ethics they give rise to, Zhuangzi asks us to remember that shi and fei, this and that, right and wrong, are merely useful linguistic categories, and not absolutes. That’s where problems arise.

Zhuangzi explains, “If a man sleeps in a damp place, his back aches and he ends up half paralyzed, but is this true of a loach? If he lives in a tree, he is terrified and shakes with fright, but is this true of a monkey? Of these three creatures, then, which one knows the proper place to live?” (trans. 1968). What is ‘right’ from one perspective may not be applicable in all circumstances. Zhuangzi is concerned about the tendency toward over confidence in one’s capacity to make “correct” judgments, when in fact these judgments are not reflective of some mind-independent state of affairs. Ultimately this can lead to undesirable consequences. Using the text’s example, if the loach tried to enforce his standards upon a man, the man would end up half paralyzed! Zhuangzi cautions us about supposing that our judgments are absolutely right independent of ourselves. We find conflict when we suppose that what we have uncovered really is the case, instead of treating our judgments like the useful tools they are, helping us navigate and make sense of the world. Conflict occurs when we elevate those judgments to the level of doctrine.

Ultimately Zhuangzi asks us to “fast the heart”. What the heck does this mean? While there are plenty of academics who might disagree with me, I’ve got the sense he’s just asking us to mellow out. If it’s a biological fact about us that we make judgments, the heart also has the capacity to revise these judgments as we encounter new experiences and events in the world. It means that instead of issuing judgments and treating them like dogma, the proper use of the heart is to critically evaluate our beliefs, to help us think in new ways, to grow, to discard old ideas, and to constantly find better ways of making sense of the changing world around us. To me, fasting the heart means to quit feeding it BS that makes us feel like we need to have it all figured out, and instead be open to growth, changing our minds, and forming new ideas and judgments as we journey on through life. It means that everyone has a story, a background, and a context and it allows us to treat each other as human beings on a journey, rather than condemn them as fools who don’t or won’t get it.

Long before I’d ever read the Zhuangzi I remember being inundated with talk about judgments and being judgmental. On the one hand, I knew I could be a little snarky cynical, and it was true that those were areas I needed to improve upon. On the other hand, I felt like I had some brain power and how could it be the case that I wasn’t supposed to or equipped to make judgments? An incredibly wise woman told me, “You can judge all you want, that’s how to know to stick with the winners – the people who have something in their lives that you want. What you can’t do is condemn. The only time we look down on someone is if we are helping them back up.” It made a lot of sense to me at the time, but has only become more profound over the years. What she meant, and what I believe Zhuangzi intends to convey, is that life is tough enough already. We have the capacity and ability to find what kind of life works the best for each of us and grow and renew ourselves each day. If we can help someone up, rather than condemning them along the way, it makes the journey all the more worthwhile.

Reference:

Zhuangzi and Burton Watson (1968). The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu. Translated by Burton Watson. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dr. Mary Riley currently administers the offices of The Institute for Creative Mindfulness and works as an assistant/manager to Dr. Jamie Marich. She received her Ph.D. in Philosophy from the National University of Singapore, specializing in warring states period in China.