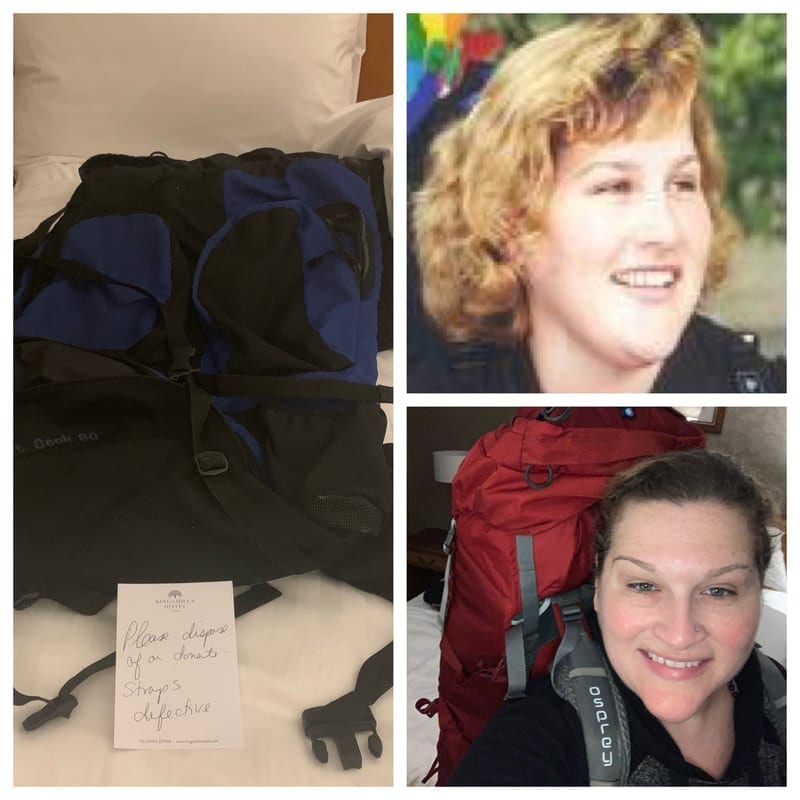

Recent events prompted me into some deep introspection about baggage and all of its metaphors and meanings. I am currently on a one-month tour of the U.K., teaching and writing. When I got to the airport, I noticed that one of the last two functional buckles holding my old girl together had cracked and broken. Over the years everything that once made the old girl an ideal backpack went bad—the waist buckle, the chest strap, some chords and zippers. The two back straps were still intact which made her still okay to use. And suddenly that was no longer the case. I checked in at Cleveland for my flight to London. Yet trying to haul a month’s worth of gear into London city from the airport with a broken backpack was exhausting. I gave her one more go as I proceeded up to Scotland last week and the strain wreaked havoc on my shoulder and back. Knowing that there was no way to fix or to replace the buckle, it was time to lay her to rest and get a new pack.

I was surprised at how difficult that was for me. I’m not really the type to get attached to material things, yet there I was, attachment sick over literal baggage.

“Wow, Buddha would have a field day with this,” I snickered.

The old girl was different. She carried me through the healing journey of the second nineteen years that sought to unravel the confusion and pain that tangled me up in the first twenty. Setting out to travel the world was a major component in my recovery for it showed me new perspectives and different energies. When I ended up moving to Europe for three years in November 2000, I carried everything I needed in the old girl. She came with me on every international trip that followed as I connected with these lost pieces of myself.

When I walked into the outdoor shop in Inverness, Scotland, I reflected on just how far that 20-year-old girl who walked into a similar shop in Krakow had traveled. Two marriages come and gone, sobriety, a doctorate, seven books written, a successful business established, major mental health relapses healed and still healing, coming out in various ways, a story of transformation still in process… Most importantly, we’ve achieved liberation by connecting to the certainly of who we really are and what we stand for—we are total and yet continually evolving towards wholeness. Traveling, embracing the journey—both literal and metaphorical—brought me these gifts.

And now the time had come to get a more functional, efficient pack for the next nineteen years and beyond. When Mark, the lovely salesman in Inverness, explained all of the features on the state-of-the-art red Osprey pack I was privileged enough to buy, my first response was, “But the pouches on the new pack aren’t like the old one—I liked that feature better!” I chuckled at myself—realizing how it’s so easy for all of us to do that during the change process. Without a doubt my new pack is better for my body, contoured for a larger woman’s back and hips and full of efficient features. This new pack is 15 gallons smaller than the old girl, which will force me to pack more efficiently. That’s probably a good thing! I knew in that moment that as attached as I can get to the things I’ve gotten used to, they may no longer be what serves me the best presently.

I’ve learned to travel lighter in the last nineteen years, both literally and metaphorically, and this adjustment certainly helps. I am also a human being struggling to make sense of attachment and heal or release the storylines I carry. In trauma focused therapy, working with attachment is a topic du jour. As an EMDR therapy trainer, I often entertain questions on how well our curriculum can help trainees to work with attachment trauma. While it’s clear that many people with complex trauma were severely wounded in early childhood by the caretakers with whom they should have formed healthy attachment, I’ve never felt that repairing attachment is the entire answer. As a mindfulness-focused EMDR program committed to East-West integration, detachment is just as important. I heartily believe the Buddha’s teaching that attachment or clinging is one of the three main causes of suffering. Yet we are human and healthy attachment is a legitimate need—so how do I reconcile this one, Buddha? Contemplating this question in meditation has taught me that acceptance and letting go are vital to the change process. We can do this at the same time as we grieve the childhood we needed and never received. We can also bring healing to the younger, wounded parts that may still live inside of us, modeling healthy attachment for them. Letting go of the storylines and the attachments that no longer serve us in the present is paramount. Letting go clears the path for healing at all levels.

I ended up letting go of the old girl in my hotel room in Scotland with a note for hotel staff to do what they saw fit. It felt appropriate laying her to rest on the international road, especially in a place as magical as Scotland. I was also blessed to stumble upon a teaching from de-cluttering guru Marie Kondo during the days I wrote in Scotland. She advises, “Have gratitude for the things you’re discarding. By giving gratitude, you’re giving closure to the relationship with that object, and by doing so, it becomes a lot easier to let go.”

I don’t think I’ve ever read anything so wise and so applicable for people on any path of recovery. Gratitude is a quality of recovery that directly helps us to let go of unhealthy or unserving attachments, yet in modern times gratitude can become so difficult to practice. We are socialized, especially in the West, to focus on what we don’t have instead of celebrating what we do. Further, practicing gratitude can feel impossible especially when you’ve been so hurt and so wronged by life and the people in it. Hopefully this will not block you from at least giving the practice of gratitude a try in your process of letting go and lightening the load.

I thanked the old girl vocally before I left the room that day, and writing this article is a way of publicly offering my thanks. Yes, it’s to an object, yet think of how much this wisdom can also help us let go of the so-called “baggage” from our past that weighs us down—memories, shame-based scripts, unhealthy coping skills, and the impact of wounding relationships. We can thank those things and those people for the role that they played for us at the time. Even the horrible stuff—if you are willing, thank it for its role in bringing you to where you are today, hopefully on the precipice of a major shift in your continued healing and recovery.